By Ramya Kumar

Healthcare is in crisis. Medical doctors, and other health professionals, are leaving the country in droves. The WHO (2010), in its Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, while discouraging the active recruitment of health workers from “developing countries” (p. 7), urges source countries to “address the geographical misdistribution of health workers and to support their retention in underserved areas” (p.8). What is the government doing to stem the health brain drain, in particular, the en masse migration of medical doctors? This article draws attention to several government policies, and proposals, that are likely to accelerate medical migration, and suggests that radically different measures may be needed.

Urban-rural inequalities

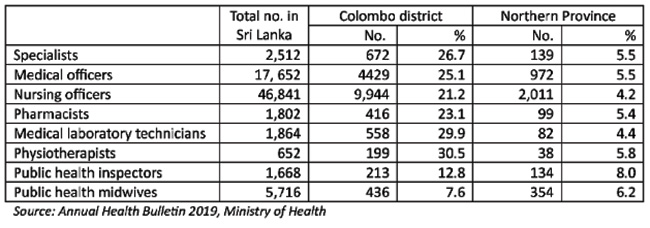

The Northern Province, which covers 13.3% of the land area and is home to about 5% of the country’s population, receives about 5% of specialists and medical officers in the state sector. Although the province receives what seems to be a fair allocation according to population size, the large land mass means that they are spread far and wide, with rural folk having to travel great distances to access healthcare. On the other hand, Colombo, where 11.2% of the country’s population resides, receives more than double its fair share, accounting for over a quarter of medical doctors, to cover just 1.08% of the land mass. While this misdistribution exists in other health worker categories (see table), the numbers show that the health brain drain will likely affect people living in rural districts more than others.

Percentage distribution of specialists and medical officers in the public sector – 2019

What have other countries done in times of crisis? Thailand has in place several policies to retain health workers in rural areas, including medical doctors. Government bonds, in place since the 1960s, require all graduating doctors to serve in rural areas for a stipulated period or pay the bond. In addition, the ministries of public health and education recruit rural students who score somewhat lower marks on national exams, to medical programmes, with specified rural service requirements to be fulfilled on graduation. The latter comprise over 30% of medical graduates in Thailand and tend to remain in public service beyond the mandated period. While similar programmes are in place to retain other health workers, health professional curricula are rurally-oriented, emphasising primary care and public health, with practical training in rural settings, with many offered in the Thai language. In addition, the Thai government offers hardship allowances, overtime payments, and numerous career advancement opportunities to incentivize rural work. The overarching goal of these policies is to improve rural access to healthcare, not constrain health workers. By contrast, in Sri Lanka, government policy seems to promote medical migration. Indeed, recent budget proposals, if implemented, may weaken existing policies that support rural retention of medical personnel.

Promoting medical brain drain

For one, no bonds are in place for medical graduates who have benefited from free education. This means that junior doctors do not need to think twice about migrating to greener pastures, with most planning to face exams to be eligible to work as doctors in other countries. Second, the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine (PGIM) sustaines a colonial policy that requires specialists to spend a stipulated period abroad to fulfill “foreign training” requirements in (mostly) high-income countries to be board certified. While the Ministry of Health forks out a (bonded) stipend for this training, it could just as well be obtained at state-of-the-art training centres in the South East Asian region that may cost less and are less likely to be destinations for medical migration.

Third, the Accreditation Unit of the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC) is presently working toward securing recognition from the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME), as its local accreditation agency. According to the Unit’s website, benefits to be accrued include MBBS holders from WFME-recognized institutions being able to register in postgraduate medical courses that recognize WFME accreditation and also seek employment in such countries. However, harmonising medical programmes in line with international requirements may neglect local needs. For instance, the SLMC’s Minimum Standards of Medical Education, gazetted in 2018, do not include requirements to complete clinical training in rural stations, despite most doctors being posted to such areas in their first appointments.

Recruitment to the state sector has halted, presumably under directives of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). While it is uncertain to what extent this policy will affect the health sector, the government should ensure that public sector employment is guaranteed to health workers in the future. By guaranteeing employment and retaining postgraduate education in the state sector, the Ministry of Health has been able to ensure the availability of specialists and doctors in the public sector. Despite politicization, in particular the influence of the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA) on transfer lists, and many other ills, this system allows the government to fill vacant rural stations with new cohorts of doctors. If public sector recruitment is halted/restricted, the uncertainties around employment may result in mass medical migration.

Privatisation and rural retention

In Sri Lanka, medical education remains under the state’s purview, delivered by 12 faculties of medicine, 11 under the University Grants Commission (UGC) and one with the Ministry of Defence. For decades, successive governments have attempted to privatize medical education. In South Asian settings especially, where most parents would like their children to follow a career in medicine, MBBS degree programmes present lucrative business opportunities. Even so, privatisation has been resisted in Sri Lanka with the SAITM debacle still fresh in our memories.

Yet, it is quite clear that the government is bent on establishing private medical schools.

Apart from the relentless attacks on student leaders, the SLMC’s Accreditation Unit welcomes applications for accreditation from all medical schools in the country; nowhere in the accreditation policy are state universities referenced. By placing accreditation in the hands of an “independent” unit, the government will be able to circumvent the UGC’s cumbersome administrative procedures, and invite foreign investment in medical education. These intentions are clear in the language used in the Minimum Standards of 2018:

“Every recognized university, or institution, within, or outside, Sri Lanka which grants or confers a medical qualification, alone or jointly with any Sri Lankan or foreign recognized university or institution under affiliation or under a twin medical programme shall ensure that the minimum standards set out in the Schedule hereto are adhere [sic] to and maintain [sic] by such recognized university or institution in the conduct of its medical education.”

Privatising medical education will shift the demographics of doctors in favour of the elite, who are far less likely to remain in the country. Contributing to these changes are the UGC’s renewed efforts to attract students with foreign qualifications, on a fee-levying basis, to local undergraduate programmes, including medicine. While a finite number of places are available at medical schools, increasing the number of students, with foreign qualifications, may see a parallel reduction in the number of local recruits within an already strained system. International medical students are even less likely to present a solution to the brain drain.

The Budget proposals for 2023 include plans to increase merit-based admissions from 40% to 50% in commerce, technology, science and mathematics A/L streams. This means that district quota based admissions to medicine from underserved districts, such as in the Vanni or Uva, will decline. While this move will deepen class-based inequalities in access to medical education, weakening the district quota system will mean that fewer rural students will enter medicine, although the latter are more likely to serve in their home districts.

Bleak future

Despite the crisis that faces the health sector, the government implements or is proposing to implement a number of short-sighted policies that are likely to accelerate medical brain drain. While the public healthcare system is in shambles, experiencing acute resource-constraints, massive changes are in the offing under World Bank-IMF pressures and what looks like a far right government. We must draw on lessons from other countries to demand the government to take measures to address the brain drain and support the retention of healthcare workers in underserved areas to avert a crisis in rural healthcare.