By Niyanthini Kadirgamar

The education system in Sri Lanka is often vilified as being outdated. But the demand for free public education has not relented. Primary and secondary schools have consistently seen high enrollments. Contrary to expectation, student numbers are increasing even in disciplines deemed less “employable”, such as the liberal arts. The Government, too, has responded to this increasing demand by pledging to accommodate more students at public universities.

At the outset, opening the gates for more youth to gain higher education seems to be a step in the right direction. However, without a corresponding increase in resources and capacities, such a move has placed enormous pressure on higher educational institutions. For the most part, university administrations and the faculty have not objected to UGC directives for expansion. The recent move by the University of Moratuwa Teachers’ Association, to voice concerns about the increase in student enrolment and their decision to refrain from work if the government fails to retract student numbers, stands out as a bold step and has awakened us to the troubling realities.

Flattening the curve?

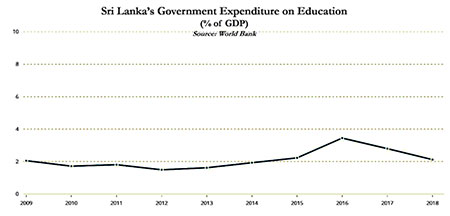

Apart from making lofty promises in election manifestos about giving education a central place in Sri Lanka’s progress narrative, subsequent education budgets have rarely reflected those ideals. Contrary to the complaints of disgruntled taxpayers about monies being wasted on free education for ungrateful (protesting) youth, the education budget has remained dismally low. As depicted in the figure, government spending on education has remained constant at an average of 2% of GDP in the post-war decade, well below the South Asian average (3% of GDP).

Excluding Bangladesh, Sri Lanka’s education budget remains the lowest in the region. Schools and universities in our free education system are running at an efficiency rate that can put even the corporate pundits of efficiency to shame. They have endured amidst significant challenges imposed by dwindling resources. Already stretched to the limit, the system may soon reach a breaking point.

Successive governments have failed to restructure investments in the social sector, including in education. In the post-war decade, under the Rajapaksa government, funding for education dipped to a dismal low in 2012, triggering strike action as part of a broader campaign led by the Federation of University Teachers’ Associations (FUTA) to demand for 6% of GDP for education. The campaign ended, failing to secure a significant increase in allocations for education.

In 2015, the challenge was taken up by the Yahapalanaya Government as part of its election drive, with a promise to progressively increase education spending within its five-year tenure. Once again, the promise was short-lived as budgetary allocations fell after an initial increase to 3.4% of GDP in 2016.

Budgets during a pandemic

Currently, we are facing a dire situation, which can only be partially blamed on the pandemic. An economic crisis precipitated by foreign debt repayment obligations was waiting to unfold even as the country elected a two-thirds majority government with a very low amount of government revenues available to spend. The Gotabaya Rajapaksa government’s budget for 2021 was apathetic, neither acknowledging the pandemic nor acting to make amends for the nosediving economy.

In the Government’s post-COVID-19 policy articulations, education has been envisioned in relation to a knowledge economy, as if such a transformation is possible during a downturn. STEM disciplines are being given priority, along with allocations for expanding distance and vocational education. The 2021 budget failed to address the immediate challenges of preventing school dropouts by offering equipment and facilities for online learning and ensuring a safe return to physical classrooms.

In this scenario of unrealistic budgetary utterances, schools and universities will be pressured to tighten their belts further this year. A revision of expenditure items is inevitable and there are signs of transferring responsibility to educational institutions by pushing them to raise funds for survival. Underfunding the public education system to ruin will pave way for more privatization, with grave implications for access.

Unequal distribution

Shrinking public funding for education is only part of the problem as the unequal distribution of those meagre allocations pose a different set of challenges. Exhausted by months of engaging in distance learning, students and teachers are now nervously returning to unsafe schools and campuses to begin the academic year, with no additional resources to confront the pandemic or economic deprivation.

Amidst the overall neglect of the sector, general education has taken the hardest hit, well before the pandemic. According to news reports it was revealed at a recent Committee On Public Accounts (COPA) meeting, that around 200 rural schools were closed between 2013 and 2018. Further, concerns were raised about the quality of education in more than 5000 schools with less than 200 pupils. In such rural schools, shortfalls of primary school teachers, along with lacking space and basic sanitary/water facilities, were identified as key problems. The situation is alarming, given the “Nearest School is the Best School” project implemented by the previous government was supposed to address those very concerns.

Disparities in resource allocation within the public education system have become even more pronounced with the pandemic, as some schools continue to fail to provide the most basic levels of hygiene – running water for washing hands. Students from rural locations and low-income households who have fallen off the grid in the haphazard transition to online learning and may not return to school this year. Without social welfare support and the incentives needed to arrest the economic decline, more children may end up the same way. The situation is especially bleak in war-torn regions where investments on education for the generations of children and youth battered by violence are yet to materialize.

Human capital logic

The World Bank announced an ambitious human capital project for Sri Lanka in 2019. Its plan for the public education system is based on the flawed assumption that the country’s economy was transitioning from a rural economy to an urban, “globally competitive” export-led economy. Human capital is the underlying thinking that has informed the reshaping of investments in education globally for the last several decades.

Proposed by the Chicago School of (neoliberal) economists in the 1960s, human capital theory assumes a linear relationship: greater investments in education enable more years of education, which, in turn, create opportunities to earn higher incomes, resulting in greater productivity. The obsession with measuring the success of education systems by the ‘rate of return’ and ranking countries based on the Human Capital Index (HCI) followed. In order to achieve higher HCI, education systems, including curricula, pedagogy and evaluations, needed to be reformulated to deliver the skills or competencies required to be a productive adult in the workforce.

Human capital is a flawed concept at many levels. Correlating more years of education and productivity, productivity and incomes, and productivity and earnings, have all been contested over the years. According to critics, access to formal paid employment is shaped by structural factors such as class, gender, race and caste, which are neglected by human capital theory. Furthermore, such a narrow understanding of education restricts the space for other ideals like democratic citizenship.

Nevertheless, human capital has entered the local policy discourse, from SLPP’s election manifesto to the President’s address at the inauguration of the new parliament, and even in the President’s meetings with unemployed graduates and education authorities where he stressed upon the development of human capital as the most valued asset. There is a clear convergence of the Government’s vision for education with World Bank’s policy prescriptions.

Confronting budgetary challenges

The current crisis in the education budget is a result of the decay in public investments over the last couple of decades. It has left the sector more vulnerable to shocks imposed by the pandemic and economic depression. How can educators respond to the budgetary challenges? There is an urgent need to confront the fallacies in both the thinking and allocations of funds and to resist the top-down approach to implementing the education budget.