By Ramya Kumar

Interest-free loans of LKR 1.1 million are to be offered for students to follow degree programmes at private higher educational institutions. An amendment to the Universities Act has been proposed to establish a Quality Assurance Council under the University Grants Commission (UGC) to maintain the quality of academic programmes offered by state and non-state higher educational institutions.

According to the government, these policies are designed to increase access to higher education and standardize the quality of academic programmes. However, the relentless attacks on the student movement, arbitrary arrests of Inter-University Students’ Federation (IUSF) leaders and the media campaigns against free education signal a different agenda: privatisation. As the government sets the stage for a ‘radical’ revamping of higher education, this article looks at what might be in store for medical education.

Minimum standards

Private medical education is a sensitive topic in Sri Lanka, so much so that the government has kept mum about its plans. The foundation for the establishment of private medical schools has already been laid through the setting up of an Accreditation Unit under the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC). The medical fraternity may oppose private medical schools of questionable standards, but does not, in principle, object to private medical education. Indeed, there is much complacency on this front since the gazetting of the Minimum Standards of Medical Education in 2018, after the SAITM debacle. Even the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA), which opposed SAITM based on ‘quality’ concerns, now simply demands that they be consulted in matters pertaining to private medical education.

It is believed that the quality of MBBS degree programmes can be assured by the requirements set out in the Minimum Standards, for instance, minimum qualifications for student admission, staff requirements, hospital bed numbers, bed occupancy rates, etc. To be sure, the Minimum Standards do set much-needed ‘benchmarks’ to check the proliferation of low-quality private medical schools.

However, by considering state and non-state medical schools on an equal footing, neither the Minimum Standards nor accreditation processes give due consideration to the impact private medical schools will have on state medical faculties. In particular, they overlook equity and justice in access to medical education.

An unhealthy symbiosis

Take, for instance, the staff requirements laid out in the Minimum Standards. In terms of academic staff, the Standards specify that MBBS degree-awarding institutions should “conform to teacher-student ratios… not less than one teacher for every 14 medical students, taking into account the permanent academic staff and the extended faculty of specialists in affiliated teaching hospitals and other healthcare settings.” They include provisions for a balance between full-time and part-time academic staff, and ask that “all medically qualified staff engaged in patient care are registered with the designated body responsible for registration of medical professions in the relevant country” (Note: the Minimum Standards apply to overseas medical schools that produce MBBS graduates who intend to work in Sri Lanka).

In the event that private medical schools set foot in the country, it is unlikely that these institutions will be able to attract diaspora medical professionals who could renew their SLMC registration, given the economic situation in the country. Therefore, these institutions would need to rely on retired medical professionals or current teaching faculty at state medical faculties. As the Standards do not place limits on teaching hours, university teachers will be able to divide their time between public and private medical schools (akin to ‘dual practice’ by clinicians) or, if the benefits are appealing, a wholesale movement from state to private medical schools may occur.

If teaching faculty engage in ‘dual practice’ in state and private medical schools, there is no guarantee that their primary commitments will remain with state medical faculties. Given the required hospital beds and occupancy rates specified in the Minimum Standards, private medical schools may need to rely on public hospitals for clinical training. For this reason, they may be located adjacent to tertiary hospitals in peripheral districts that do not serve as clinical training centres for students of state medical faculties.

Winners and losers

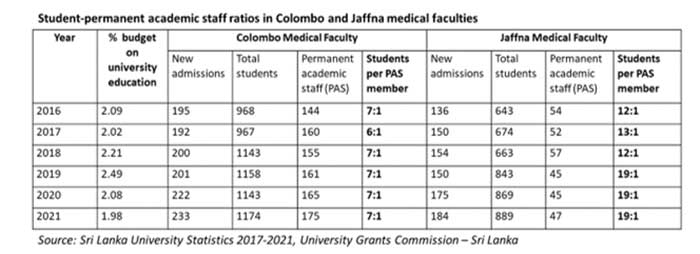

Student intake to state universities, including medical faculties, has steeply risen in recent years (see table). Even so, the Colombo Medical Faculty has been able to maintain its student to permanent academic staff ratio at 7:1. Owing to its location, the Colombo Medical Faculty would be able to attract medical professionals to full-time teaching positions despite the higher salaries offered by the Ministry of Health.

However, the student to permanent academic staff ratio at the Jaffna Medical Faculty has risen over the years, climbing to 19:1 in 2021. The availability of vacant cadre positions at Ministry of Health institutions in and around Jaffna gives medical professionals no reason to resign from the Ministry to take up teaching positions that pay substantially less. (See table)

The requirement of 14:1 is fulfilled by state medical faculties in peripheral districts when temporary staff and extended faculty at teaching hospitals are considered. Yet, curriculum development, ‘quality assurance,’ student welfare and other time-consuming activities are undertaken primarily by permanent academic staff. If private medical schools are established in such districts, state medical faculties will need to compete not only with the Ministry of Health, but also with private medical schools that can offer much higher salaries, causing a dearth in teaching staff at state medical faculties.

Equity of access

The government will gloss over equity concerns by promising loans, voucher schemes and other carrots to study at private medical schools. Even as the state university system as a whole is seeing declines in state investment (see table), and even more so after the economic crisis, it is unclear how these loans will be financed. Accumulating student debt has shown to influence the career choices of medical students in other settings.

As the country struggles to retain medical professionals, it is unlikely that medical graduates burdened by student debt will serve in the public health sector under the present salary structure. It is even less likely that fee-levying international students, the government’s primary target for forex, will serve in Sri Lanka’s health sector. In other words, whether private medical schools will produce medical professionals to service the healthcare needs of ordinary citizens is uncertain.

The entry of private medical schools will change the demographic makeup of medical students by creating a two-tiered system of medical education. Given the emphasis on student resumes and ‘soft skills’, not to mention the hefty fees that will be levied, those who enter private medical schools will mostly represent the middle/upper-middle classes. According to UGC statistics, in 2020/2021, about 63% of enrollment in state medical faculties was through the district quote system. While the Colombo elite suggest that this is a form of reverse discrimination, such arguments overlook the tremendous disadvantages experienced by students from rural districts.

A closer look at the UGC’s admission statistics of 2020/2021 shows that the majority of students who entered medicine from the Vanni districts, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Moneragala and Nuwara Eliya, did so through the district quotas. With the entrenchment of private medical education, and weakening of state medical faculties, the opportunities for students from rural and plantation districts to access medical education will contract. It must be remembered that it is also these students who tend to populate peripherally located state medical faculties.

Ideology in the making

As health professionals leave en masse from the country, it is argued that private medical schools might present a solution for physician brain drain. The entry of private medical schools will surely create a two-tiered system with lasting impacts on who has access to medical education and on the healthcare system more broadly. Until now, state medical faculties have furnished the public health sector with its medical cadre. While there is certainly room for improvement, at this point, the focus should be on supporting state medical faculties to ensure the survival of the public health sector.

As welfare is steadily chipped away in the name of the economic crisis, the government, supported by sections of the elite, suggest that it is a ‘welfare mindset’ that has brought the country to this state of crisis. The media is drumming up support for the government’s short-sighted policies, including the dismantling of free education. Images of student protests are being deployed to further delegitimize state universities, detracting attention from the ongoing mass-scale dispossession that is taking place in this country, whether through ‘domestic debt optimisation’, labour reforms or the proposals on restructuring higher education and public health. In this context, opposing private medical education is portrayed as ‘ideological’ or impractical, concealing the ideological work that has been undertaken over the years to convince many to believe that fee-levying university education is the way forward.