By Ramya Kumar

Global inequality is at an all time high. According to a recent Oxfam report (Inequality Inc. January 2024), the richest 1% of the world owns 43% of global assets; the world’s richest five men have doubled their wealth since the onset of the pandemic while five billion people have been made poorer. Ever-reducing wages (for workers), tax concessions and evasion (for/by corporates), and the privatization of public services has concentrated wealth and power in corporates, increasing their influence in every policy domain, says Oxfam.

In Sri Lanka, the pandemic and ensuing crises have seen real wages halved, VAT hiked and income taxes for the wealthiest capped at 30%. The government is cutting public spending as per IMF targets and swiftly selling off public assets, including state-owned enterprises, natural resources, and public services. Along these lines, the recently unveiled National Education Policy Framework 2023 (NEPF) seeks to transform education by ushering in the private sector. While the NEPF has been produced at the bidding of an illegitimate Parliament and warrants wholesale rejection, this article examines the ideological underpinnings of the NEPF and their implications for higher education.

Ideology at work

NEPF’s stated goal is to “sustainably enhance the access, quality, relevance and digital transformation of the education system through systemic changes to the [sic] teaching, learning and credentialing; governance; and investments and resources domains to expedite economic and social development.” One of the NEPF’s seven policy objectives is to assure access to education for “all children, irrespective of race, ethnicity, caste, religion, nationality, language, income, or disability” (p.5). How does the NEPF propose to achieve this objective in the realm of higher education?

The main thrust of the policy appears to be to expand the role of the private sector in higher education. To this end, the government will facilitate “participation of non-state partners, including public-private partnerships… in all sectors” (p.28). Most strikingly, the Free Education policy, specifically non-fee levying tertiary education, may no longer be a reality as the reforms support a demand-side model where students will pay for their education with “government grants, government-backed loans, and out-of-pocket contributions” (p. 28). Notably, “the distribution of each and the related formulae, including criteria for merit and ability to pay” are yet to be determined (p.28). Precisely how the NEPF will ensure access for students from underprivileged districts receives no mention in the policy.

The NEPF expects to bring state and non-state higher educational institutions (HEIs) under a National Higher Education Commission (NHEC), replacing the University Grants Commission (UGC) (p.26). This move will place private HEIs on par with state universities, all of whom will now be required to compete with each other for public funds. “Students receiving government grants and government-backed loans [will] have a choice of enrollment in state or non-state tertiary education institutions”(p. 9). Further, a period of three years will be provided for “universities to transition from line-item based funding to enrolment-based funding” (p.28). As grants will be performance-based, the policy will effectively penalize universities located in peripheral districts. For instance, a student who might otherwise enroll at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, will now have the choice of selecting a private medical school, located in Colombo. As state universities fail to attract students, they will be weighed down by resource-constraints, amplified by brain drain, even as the removal of “limits to ownership by foreign investors in higher education and skills development” (p. 29) may pave way for wholesale buyouts of state assets.

Among NEPF’s policy objectives is a pledge for “equal opportunity for digital learning and digital literacy for all children.” While overlooking dire resource constraints, such as the lack of residential facilities in the face of a 30% hike in admissions since 2019, as well as other services essential for health and wellbeing, it places emphasis on digital technologies and artificial intelligence. Many have highlighted the inordinate profits made by Big Tech during the pandemic and their growing influence on education systems struggling amidst fiscal constraints. This focus on digital technologies will expand markets for Big Tech and the education industry in the global South as public resources are channeled towards “ed-tech.” While the ideological slant of NEPF is obvious, the policy offers ill-conceived solutions to misrecognized problems.

Misrecognition

The NEPF opens by stating that only 8.9% of students in Sri Lanka are admitted to state universities, echoing what various policy analysts have been drawing attention to for some time. These numbers are usually attributed to the “monopolization” of the higher education sector by state universities. Can the low tertiary education enrolment rate be blamed on state universities? UNESCO measures enrolment in tertiary education as the ratio of total enrollment, regardless of age, to the population in the country that corresponds to the specific level of education. At 21.36%, Sri Lanka ranked 87th out of 109 countries in 2021 (range: Greece 150.2%, Malawi 2.41%). Noteworthy here is that the denominator (the population that corresponds to the specific level of education) includes those who did not qualify to enter universities—over a third (37.6%) of students who sat their A/Ls in 2021, according to UGC sources. Just under a quarter (24%) of those who did qualify for university entrance were selected to state universities.

In order to increase tertiary education enrollment rates, larger structural issues in the education sector need to be addressed. For one, spending on education is abysmally low. UNESCO recommends that governments spend 4 to 6% of GDP on education. In Sri Lanka, government expenditure on education was a mere 1.2% of GDP in 2022, the second lowest in the world (World Bank Open Data, 2024). Surprisingly, the NEFP does not reference this problem! Rather it states that the education transformation envisaged by the policy will be funded through “the redeployment of existing resources, leveraging of additional resources through partnerships with non-state entities, and private contributions.” In other words, the government does not intend to increase investment in education anytime soon, although it will subsidize the private sector through the provision of government grants and student loans (p.29). However, state universities deliver education to about a quarter of qualifying students on a very small budget (a mere 0.06% of GDP in 2023 according to our calculations). It would make financial sense for the government to increase the capacity of the state university system to address the shortfall of university education, rather than incentivize the private sector, which will likely turn out to be a costly affair in the long-term.

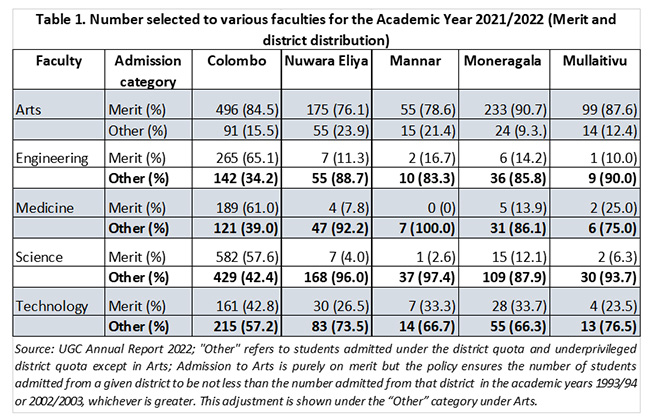

The wide (and deliberate) discrediting of state universities has made us blind to crucial questions of access. Focusing on numbers has served to obscure the fact that state universities provide opportunities for young people from disadvantaged districts who may have no other options for higher education. Table 1 shows the distribution of students selected to various faculties in 2021/2022 by their admission category. Noteworthy is that the majority from Colombo district enter under the merit category, while most students from underprivileged districts enter through the district quotas—currently at 60%. As described in the footnote, the UGC implements various mechanisms of affirmative action in student admissions to bridge inequalities in access to education experienced in rural or disadvantaged districts. It is such a system that remains free at the point of use with in-built mechanisms to address inequalities that will enable students who would otherwise be left behind, to access education, including in the much-coveted STEM programmes that are being promoted by the government. (See Table 01)

The NEPF presents student loans as a feasible financing mechanism for higher education. As Farzana Haniffa showed us in Kuppi (October 24, 2023), student loans have proven unsustainable in many settings with many defaulting on repayments. Student debt is also known to influence career decisions. For instance, in medicine, student loans drive junior doctors to select more lucrative career pathways. Policymakers must reflect on whether universities should create graduates who will be drawn to high-paying jobs or whether we would like our graduates to be involved in service-oriented occupations.

Back to inequality

Whether through privatisation of education, the removal of subsidies from public utilities, exploitative labour reforms or domestic debt restructuring, the economic crisis has proved devastating for the 99%. According to the UNDP, the top one percent of Sri Lankans owns 31% of the total personal wealth, while the bottom 50% owns less than 4 percent. What we need right now are policies based on social justice to bring us out of this crisis. Yet, the government is bent on rolling back advances in social development that the country has made in its 75-year post-independent history. Dismantling Free Education will surely see the demise of any government who dares to venture down such a pathway.